The terms "dairy alternative," "dairy-free," "

plant-based," "Chick'n," "Chickun," "Bacun," "Cheeze," and "plant butter" are standard on Canadian store shelves.

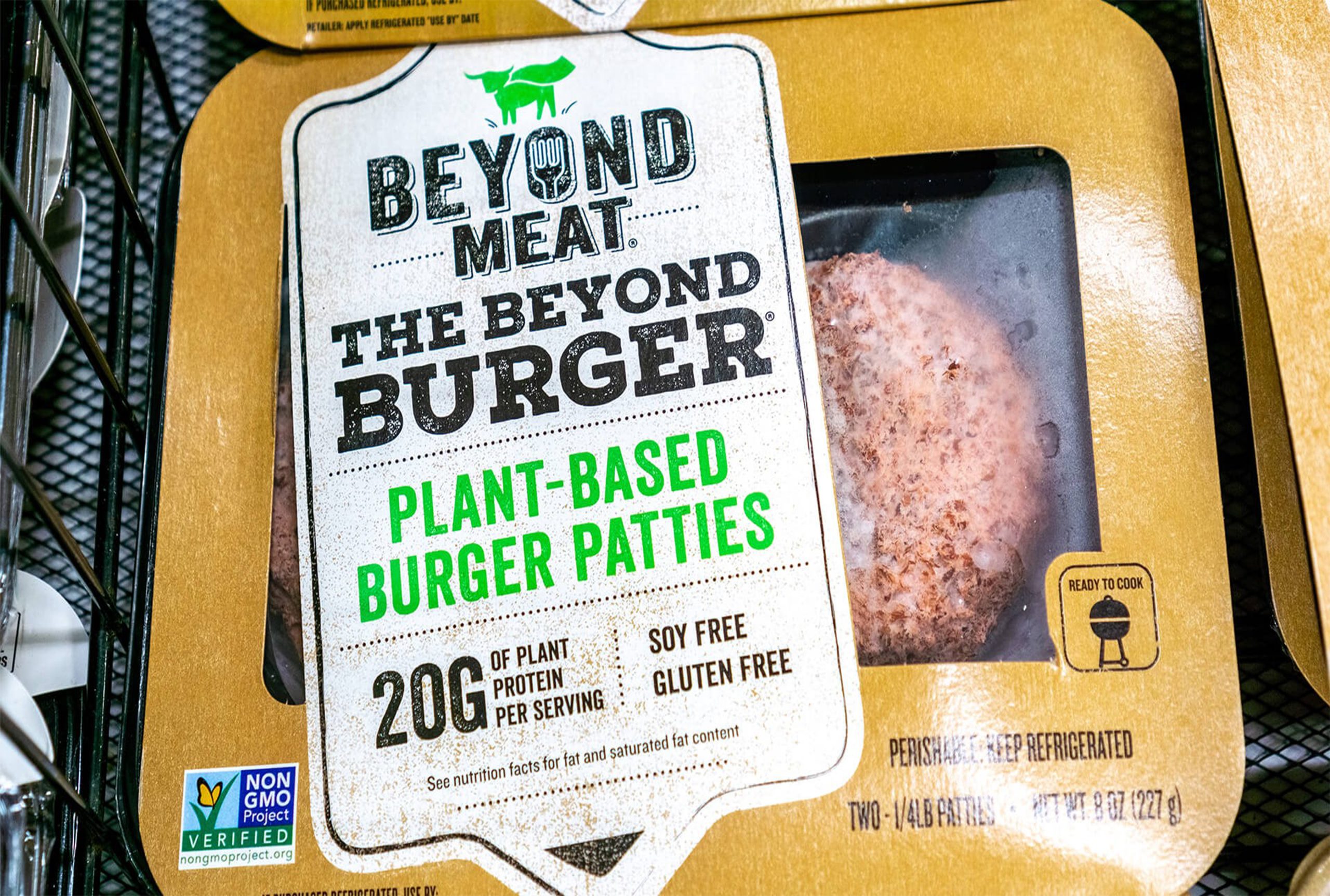

There's indeed been a meteoric rise in the availability of vegetarian and vegan alternatives to meat, poultry, and dairy.

Labeling

Problems with labeling are inevitable whenever a new type of product is introduced. In Europe and the United States, naming

plant-based beverages with common names like "milk" has caused controversy.

Cornell University researchers also found that using words commonly associated with animal products (like "milk," "cheese," or "burger") in the name of a

plant-based product did not lead buyers to assume that the product was derived from an animal incorrectly. Researchers found that consumers were significantly more confused about the flavor and uses of

plant-based products whose names omitted words typically associated with animal products.

Advancements in Canada’s Plant-Based Foods Regulations

Using common names like butter, cheese, meat, and milk to identify

plant-based foods is currently prohibited in Canada, according to Leslie Ewing, executive director of Plant-Based Foods of Canada (PBFC), a division of Food, Health & Consumer Products of Canada. PBFC has suggested that Health Canada reevaluate its regulations regarding using popular names for plant-based food products; these regulations currently include qualifiers where they are deemed necessary. The use of terms like "plant-milk," "soy-milk," "plant-butter," or "soy burger" on the label would make it abundantly clear that the item is plant-based, vegan, or vegetarian. Section B.01.100 (1)-(4) of the Food and Drug Regulations mandates the labeling of plant-based products as "simulated," which PBFC has urged Health Canada to repeal. PBFC thinks this is unnecessary and will only confuse shoppers, as terms like "plant-based" clarify that the product does not contain meat.

When asked what kind of labeling framework it would prefer for

plant-based products, the Canadian Meat Council (CMC) said that it "advocates for accurate and truthful labeling of goods while supporting the enforcement of fair labeling by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency" (

CFIA). Regarding purchasing decisions, CMC is all for giving customers more options. The same strict regulatory requirements for livestock

agriculture also apply to plant-based products that mimic real meat.

Those sentiments are shared by the Canadian Poultry and Egg Processors Council. Plant-based foods must be labeled to make it clear that they are not the same as meat, chicken, or eggs. For example, this means that "simulated meat" and "plant-based product" should both be included in the common name of any plant-based product sold in the market.

CFIA held public hearings in November 2020 to solicit feedback from consumers and businesses on draft guidelines detailing faux meat and poultry rules.

CFIA will also use the comments from the consultation to revise its regulations for

plant-based foods that are not meant to replace meat or poultry.

CFIA notes that future guidelines will not address packaging particularly, but rather the overall portrayal of the food product when discussing the appearance of

plant-based substitute goods like plant "butter" that looks very similar in shape, size, and packaging to a rectangular shape pound of cow milk butter. The information on a label cannot be deceptive. Accurately representing foods and avoiding confusion with other

food manufacturing.

Required Certification for Plant-Based Foods

PBFC stated in early May that many items bearing the Certified Plant Based certification are now available in Canadian supermarkets. Plant-Situated Foods Association is based in the United States and owns this certification methodology. They collaborated with PBFC to develop the Canadian version, which includes meat, poultry, egg, dairy, and seafood alternatives derived from plants. Independently certified by NSF International.